They Mocked Me at My Brother’s Funeral, Then a Jet Arrived to Get “The General”

My name is Rachel Monroe. I flew combat missions for the Air Force for nearly two decades, logged over 3,000 hours, survived one crash and two deployments that still visit me in my sleep. But none of that ever made it into the family Christmas letters, and it sure didn’t earn me a spot on the guest list for my brother’s funeral.

I arrived just after sunrise, parked two blocks down from the chapel, and walked the rest of the way in uniform under a civilian coat. No one noticed. That’s how it had always been—me slipping in and out of the family’s life like a shadow they never quite acknowledged.

The church doors were already open. Rows of black suits and polished shoes filled the pews. There was a printed program in every seat, embossed in gold. His name was on every page. Mine wasn’t even in the acknowledgements. They always said I made choices they didn’t understand, that my path made it hard for them to relate. But I never asked for applause. I just wanted to matter enough to be included.

When my brother Daniel died, it was sudden. Heart attack in his sleep. Forty-four years old. No warning. The family came together like clockwork—perfect grief in perfect suits. I was told by voicemail. They didn’t expect me to come. Probably assumed I was too far away, too unreachable. I didn’t correct them. I just showed up.

Inside, I took a seat in the very back behind the last row of mourners near the stained-glass window. It was the same church we’d been dragged to as kids. I remembered tracing the cracks in the wooden pews with my fingernail while the sermons went on. I did that now, too, out of muscle memory.

I saw my parents up front—my father with his hand resting on my mother’s wrist like a punctuation mark. Her face set in stone, eyes dry but dramatic, the kind of sorrow meant to be witnessed. I hadn’t seen them in four years. The last time was a family wedding I wasn’t invited to, but attended anyway. That was also the last time we spoke—briefly, at a distance, like diplomats from estranged countries. They hadn’t changed, still wrapped in the world they built for themselves. One where Daniel was the golden sun and I was the cautionary tale they didn’t explain to new friends.

I listened to the eulogy—stories about Daniel’s firm, his charitable giving, and how he coached Little League. Even after a full week at the office, they called him a leader, a mentor, a pillar. I waited for my name. It never came. No one turned around. No one whispered. I wasn’t important enough for scandal or sympathy. I was a ghost in a borrowed pew.

But I didn’t come to be seen. I came to remember what being invisible felt like, because something had shifted. And soon the silence they once counted on was going to be broken.

The pastor’s voice carried through the chapel like a soft command, reverent and practiced. He spoke of Daniel as if he’d been a soldier, a saint, and a CEO all-in-one. Every sentence was polished, every anecdote curated to present a man who never failed and never faltered. I sat there listening, knowing full well how carefully that version had been built.

Daniel had charm. He had polish. He knew how to say the right thing in front of the right people. That was enough for our parents to crown him before we were even teenagers. My mother wore a tailored navy dress, pearls resting like punctuation against her collarbone. She dabbed her eyes occasionally, but her makeup stayed intact. My father kept his hand on her arm, nodding solemnly as old business partners and neighbors whispered condolences.

To them, this was a gallery of grief, and they were the curators. Every gesture rehearsed, every response deliberate. There was no room for raw sorrow here, only display.

I watched them stand for the family tribute. My father adjusted the microphone, cleared his throat like he was addressing a boardroom, not mourning a son. He thanked everyone for coming, praised Daniel’s career, his family values, and his impact. He ended with, “We were lucky to raise a son who made us proud every single day.” Then he sat down and that was that. No mention of the girl who used to build Lego cities next to Daniel’s train sets. No nod to the sister who once pulled him out of a frozen lake when he fell through.

My existence wasn’t erased. It was simply inconvenient. It had always been that way. Daniel got the new bike and I got the leftovers. He got private school. I got scholarships. When I enlisted at seventeen, they told friends I was “figuring things out.” When Daniel opened his first office, they sent out announcements. At some point, I stopped trying to prove anything. Not out of strength, but because exhaustion feels a lot like acceptance if you sit with it long enough. I stopped sending holiday cards. They stopped noticing.

Today was no different, except for the fact that Daniel was gone. And even in death, he pulled them all tighter together, like I was the outside ring no one remembered to draw. The organist played something slow and mournful. People dabbed at tears, cleared throats, shifted in their seats. I just stared at the back of my parents’ heads and wondered what it would have taken for them to ever say they were proud of me. Maybe if I’d stayed. Married young. Settled into something they understood. But that version of me never existed, and they never tried to find the one who did.

A woman two rows up leaned into my mother and whispered something. My mother smiled faintly and replied, “Daniel always had a sense of purpose. Rachel was more restless.” The woman nodded politely. My stomach tightened, but I didn’t move. They always used that word—restless—like I was a windstorm that couldn’t sit still, not a woman who carried lives across airspace or helped stabilize wounded pilots in hostile terrain.

I stayed in my seat until the recessional began, until the polished casket rolled past and people murmured blessings they barely meant. I didn’t join the procession. I didn’t step into the sunlit parking lot with the others. I waited, because sometimes the only power you have left is not giving them what they expect.

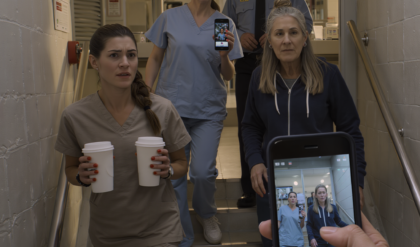

The sound came low at first, a steady rumble that rolled across the chapel roof like distant thunder. People paused midstep, glancing upward as the windows trembled in their frames. A few shifted uneasily, unsure if it was part of the service or something else entirely. Then it hit—a deafening roar as the military jet streaked overhead, banking hard before dropping altitude fast. The stained glass rattled and somewhere in the back, a baby started to cry.

Gasps filled the room as the jet came into view through the tall windows. Sharp angles, gray steel, unmistakably government-issued. Phones came out, people pointing, whispering, turning toward the double doors at the back.

The engine noise softened just enough to make room for what followed: a pair of boots hitting the pavement outside. Then the doors swung open and a uniformed officer stepped inside, hat tucked under his arm, expression unreadable.

“Brigadier Monroe,” he called, voice clear and cutting through the stunned silence. “You’re requested for immediate transport, priority red.”

Every head turned. People shifted in their seats. A few whispered my name, finally seeing what they had spent years pretending not to. I stood without rushing, folded my coat neatly across the back of the pew, and stepped into the aisle. The officer snapped to attention as I approached, offering a crisp salute. Somewhere near the front, I saw my mother’s face freeze. My father’s jaw tensed. A woman near them dropped her program.

For the first time in years, I wasn’t the one arriving unnoticed. I wasn’t the quiet one in the back row. I was the headline they hadn’t written—and they didn’t know what to do with that.

The jet’s roar still echoed in the rafters as I walked down the aisle. People parted like water, unsure whether to step aside or stare. No one spoke, but their eyes shouted what their mouths couldn’t catch up to. At the front, my father stood slowly, like his body had to catch up to the reality unfolding. My mother blinked hard, her mouth slightly open, a smile halfway formed and quickly swallowed. The officer held the door for me.

Before stepping out, I turned just enough to meet their eyes. I gave no smile, no nod—just let the silence do what words never could.

Outside, the air smelled of jet fuel and grass scorched by heat. A black SUV had pulled up near the chapel steps, and beside it, a man with a press badge lifted his camera and snapped three quick photos. I didn’t flinch. Neither did the officer. But behind me, I heard murmurs start to bubble, curious questions, half-recognized titles, and one hushed voice saying, “Is that—?”

The photographer stepped closer, clearly tipped off by someone. Maybe he’d been sent to cover the funeral of a local businessman and stumbled onto something bigger. I saw the moment he realized I was the story now. My boots clicked against the concrete as I crossed to the car. The door opened. I paused for one last look at the chapel. They were still frozen in place, my parents surrounded by whispers that weren’t scripted. It was the first time I’d ever seen them unsure of their role. And I carried that image with me as I climbed into the vehicle—quietly, proudly, finally seen, but on my terms.

The alert came through a routine audit. A line item in my pension summary didn’t match the monthly deposit. It was small, almost forgettable, but something about it felt off. I pulled the reports, cross-referenced years of statements, signatures, and benefit transfers. One document had my digital ID, but not my authorization stamp. That wasn’t possible. I never signed it. The date listed was during my last deployment, when I was off-grid in northern Syria with no access to secure systems.

I kept digging—request after request. Some were buried under civilian proxy permissions I’d never granted. One flagged entry had a power of attorney document attached with my name and a signature I recognized—but not as mine. It was clean, almost too clean. No pressure inconsistencies, no pen drag—digitally rendered, not handwritten.

I traced the access log. It originated from a residential IP in upstate New York. Pinged off a home network labeled “Monroe guest.” That’s when my stomach dropped. There was only one Monroe household with access to my personal identifiers: my parents’ home, the one my mother still lived in.

I requested full beneficiary records from the DoD pension system. The next day, a sealed file arrived with one name highlighted in yellow: secondary access listed under all three flagged accounts—Margaret L. Monroe, my mother.

I stared at the screen, jaw locked, trying to process what that meant. Either she knew what she was doing or someone used her name, too. Either way, the betrayal came from inside the circle. I called the audit office, asked for any communication records tied to the flagged forms. They forwarded a transcript of a fax sent in 2019. It authorized emergency disbursements due to family medical hardship. The listed contact was a landline I hadn’t used in a decade. The signature block was mine, but again—perfectly smooth, too perfect.

I called in a favor from an old JAG contact. She ran a forensic scan on the file. Within hours, she called back. “It’s a forgery,” she said. “Whoever did this had access to your full credential set—not just ID, but biometric templates. That kind of access doesn’t come from guesswork. It comes from familiarity, from someone who thinks your name belongs to them.”

I sat at my desk, hands clenched around a printout of the forged signature. Betrayal didn’t always scream. Sometimes it showed up in black ink on government letterhead. And this time it wore my mother’s name.

I didn’t call ahead. I showed up at the house I hadn’t visited in six years, walked through the side gate, and rang the bell like a stranger. My mother answered in a robe, hair pinned, surprise flickering just long enough to register. “Rachel,” she said, soft but wary, like she wasn’t sure which version of me had shown up.

I stepped inside without asking and placed the printouts on the kitchen table. She read them in silence, her lips pressed into a thin line, eyes scanning too fast to pretend this was new information.

“It wasn’t what you think,” she finally said, folding her arms like it gave her some kind of defense.

“Then tell me what it was,” I said, voice level but tight. “Because it looks like you signed my name and rerouted thousands of dollars from my account.”

She didn’t flinch, just sighed like I was overreacting. “We were behind on the house. Your father had medical bills. Daniel’s kids needed help. It was just there.”

“It was mine,” I said. “Not yours to use, not even to consider.”

“You were gone,” she said, eyes narrowing. “Always gone. We thought you wouldn’t notice.”

I stared at her, stunned by the ease with which she said it—like my absence was a reason, not an excuse. Like vanishing me from the paperwork was just logistics.

“You didn’t even ask,” I said. “Not once.”

“It was temporary,” she said. “You were always so proud. You wouldn’t have said yes.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I wouldn’t have.”

She shrugged. “It’s not like we spent it on ourselves. It went to the family.”

“You spent it on the family you chose to keep,” I said, “while erasing the one you sent away.”

Her eyes flashed, but she didn’t respond. That was the real wound—not the money, not the forgery, but how simple it had been for her to justify.

I left the documents on the table and walked out without another word. Some silences are earned; others are built—brick by brick, name by name. Today, mine came off her wall for good.

The rotunda at the Hall of Honor was quiet, except for the sound of boots on polished tile. Sunlight filtered through the high windows, casting long beams across the marble floor. The walls bore names etched in stone—none of them mine until now. I stood at attention in full dress uniform. My medals aligned, my service record read aloud without exaggeration or omission—just facts. Seventeen deployments. Fourteen rescues under fire. One crash. No shortcuts.

The officer presenting the medal had served beside me once, years ago, in Kandahar. He kept his speech short, precise: for distinguished service, operational excellence, and unwavering courage under fire. Then he pinned the medal to my chest and stepped back. I didn’t look for my parents. They weren’t there. This moment wasn’t built for them. It wasn’t choreographed for family photo albums or hometown newsletters. It was for the ones who knew what it meant to survive—not just to be admired.

Rows of uniforms filled the seats. Some faces familiar, others new, but every gaze steady. Every nod meant something. These weren’t people who needed to be impressed. They just needed to know you’d earned your place.

When I stepped to the podium, I didn’t talk about the missions or the medals or the months of recovery with steel in my back and silence in my phone. I said only this: “I didn’t come here to be seen. I came because I kept showing up—even when it cost me.”

There was no applause. Just the kind of silence that carries weight. The kind that means you’ve said enough.

Afterward, I walked alone through the lower corridor of Fort Caldwell—past restricted zones, past plaques, past reminders of the job and the people who gave more than I did. I paused in front of one frame. Inside was a black-and-white photo from Operation Iron Crest. My first mission. Five of us in the shot. Only two are still alive. I placed my hand on the glass and exhaled. Not from grief—from gravity. There are ceremonies you don’t get to attend—the ones held behind your back. The ones that erase you. This wasn’t one of them. This was the ceremony they couldn’t rewrite. A record they couldn’t adjust. A moment that didn’t need their approval to matter.

I didn’t need my name in their stories anymore. I had written my own, and for the first time in a long time, it stayed exactly where I left it.

She arrived without calling. The gate guard buzzed my office and said there was a civilian visitor named Monroe claiming family clearance. I said, “Let her in.”

She looked smaller than I remembered. Maybe it was the civilian clothes. Maybe it was the weight of knowing the script she’d rehearsed wouldn’t work here. She carried a manila folder like it might fix something.

I didn’t offer her a seat—just stood behind my desk and waited. She took a breath, then said, “I never meant for it to feel like a betrayal.”

I didn’t answer. That word feel made it clear she still didn’t understand.

She stepped forward and placed the folder on the desk. “Everything’s in there,” she said. “Every transfer, every document. I’ve withdrawn from the accounts, closed the access.”

Still no apology—just math and paperwork. She straightened her shoulders and added, “We did what we thought was necessary at the time.”

I opened the folder. The signatures were real this time. So was the notarization. I flipped through each page, then closed it again.

“You won’t be hearing from legal,” I said. “But you won’t be hearing from me either.”

She swallowed hard. “Rachel, you’re still part of this family.”

“No,” I said, voice even. “I was an asset until I stopped being useful.”

She looked like she wanted to argue, but the words didn’t come—just that same tight smile she’d worn at Daniel’s funeral. A habit more than a feeling.

I slid the folder back across the desk. “This stays here. You don’t.”

She hesitated, then picked it up slowly. “Is this permanent?”

“It’s overdue,” I said.

She turned toward the door, paused once, then kept walking. No tears. No breakdown. Just distance finally made visible.

When the door clicked shut, I sat down and stared at the space she’d left behind. It didn’t feel empty. It felt intact. Some goodbyes don’t need ceremony. They need clarity. Today I got mine.

The office was quiet—just the hum of the overhead light and the steady click of my pen. I opened a blank folder and wrote my name at the top: Rachel Monroe. No ranks, no titles. Just the name, as it always should have been—untouched, undiluted.

I slipped in copies of the corrected records. One of my original oaths. One of the ceremonies. One faded photo of Echo Unit, edges worn from years in a side pocket—the ones who never asked me to prove who I was.

Some names get spoken loudly. Others survive in silence. Mine had lived both lives. I used to think legacy was about who remembered you—what plaques bear your name. Now I know it’s about who you are when no one’s looking, what you choose when no one’s clapping. I’ve walked back into fire for people who never knew my name and still would, because that’s who I am. Not because of them—in spite of them.

Tonight, I closed the file and placed it in a locked drawer. Not to hide it—to keep it. What matters now isn’t that they forgot me. It’s that I never did. I carried myself all the way here—scar by scar, step by step. And in doing that, I reclaimed something no one can forge: my name, my story. Mine.

PART II — The Day After the Jet

The morning after the jet carved its name across the chapel sky, I woke before my alarm. The world had the crisp, just‑washed look that comes only after a night storm—street a darker black, leaves rinsed of dust, air smelling faintly of copper and rain. I brewed coffee, black, and stood at the sink while the kettle hissed. There is a specific quiet that follows public moments: a hush that asks, now that they saw you, who are you?

I didn’t answer the question out loud. I put on running shoes and took the long loop that skirts the river and the old rail yard, past the brick warehouses that now sell artisan ice cream and tiny plants in terracotta. A boy on a scooter flashed a gap‑toothed grin as he passed. Somewhere a flag snapped to attention in the wind. Somewhere a dog argued with a squirrel and lost. My body found its rhythm, feet making that soft, convincing percussion that says, yes, you’re still here.

By the time I showered and turned on the phone, the world had rearranged itself into notifications. A reporter I didn’t know had emailed twice. A local news blog had posted drone footage of a gray triangle slicing the morning. Three messages from people I remembered as faces and first names: Saw you yesterday. Proud of you, General. You always kept your spine. Call if you need anything. I didn’t answer any of them. I sent one text to the officer who’d stepped into that chapel and said my name like it was a fact that could not be edited.

Good extraction. Clean lines. Thank you.

He replied: Anytime, ma’am.

I set the phone face down, opened the window, and let the cool air climb the curtains.

The Briefing That Wasn’t About War

At 0900 I stood in a room that smelled faintly of old carpet and fresh printer toner. The slide on the screen behind the briefing officer was labeled OPSEC AND FAMILY in the kind of sans‑serif font that thinks it’s being friendly. A handful of us were there—people who had seen enough and yet still found new ways to be surprised. The officer, a major with the easy competence of someone who could do ten different jobs and make you think it was one, nodded toward me once and then got down to business.

“Public bleed‑through,” he said, clicking to an image of the chapel—frame frozen on the moment the doors blew wide with sunlight. “It happens. When it does, we don’t apologize for the work. We also don’t pour gasoline on the embers.”

No one looked at me. No one needed to. We talked through protocols—how to route press inquiries, how to say nothing without sounding like a stone wall, how to keep the men and women who rely on you from becoming collateral damage in someone else’s headline. At the end, the major’s eyes flicked to me again. “General Monroe? Anything to add?”

“Just this,” I said. “Silence isn’t always secrecy. Sometimes it’s stewardship.”

He smiled like we’d just shared a good inside joke. “Copy that.”

The Call from the Boy with the Scooter

Two days later, a voicemail: “Hi, um… General? It’s Mason. The scooter kid. My mom says I shouldn’t bother you, but she also says I should write thank‑you notes, and this is like that only not a note. Thank you for… the way you walked out of that church. My grandma says now I don’t have to apologize for being good at things.” He paused, breath loud in the microphone. “Also if you want to see my volcano science project explode, it’s on Saturday.”

I saved the message. I marked Saturday on my calendar. I knew I probably wouldn’t be there. I liked the idea that I might.

The Letter I Didn’t Send

I wrote a letter to my parents that night and didn’t send it. Not a performance letter. Not a grenade. Just a simple account of the last twenty years as I had lived them, minus heroics and minus bitterness: bases with names that sound like cover stories, friends whose funerals we held on airstrips because there was nowhere else to put that much sky, the mechanics who kept us up and the medics who kept us human. I listed Daniel’s jokes I still remembered. I listed the makeshift birthdays I spent on missions, the cakes cut with a survival knife, the candles we didn’t light.

Then I folded the pages, slid them into an envelope, and tucked them into the back of a drawer, next to a coin I’d been given by a crew chief who’d taught me how to trust my instruments when my gut was too loud. Not everything you write needs to travel.

Echoes of Iron Crest

You tell yourself the first crash recedes. It doesn’t. It changes shape. On quiet nights it becomes geometry—angles and speeds and the exact feeling of metal not obeying anymore. On loud nights it becomes a taste: battery and carbon, the grit of dirt in your teeth when you finally stop moving.

Iron Crest was ten thousand years ago and last week. The weather had been printed on the briefing slides as “variable,” a word that should be retired from forecasts and reserved for hearts. We were heavy with fuel and human urgency. We had done everything correctly, and then the wind forgot to read our checklist.

We lived. We did not all live. I don’t talk about that day because the story belongs to five families, not one translator. What I will say is this: when I woke up strapped to a stretcher in a tent that smelled like antiseptic and salt, the first thing I saw was a young mechanic standing next to the cot with grease on his cheek like war paint. He held my dog tags like a rosary. He said, as if we were continuing a conversation we’d started on a better day, “Ma’am, your bird did what you asked her to until the sky stopped being reasonable.”

I nodded. It was the only absolution I ever needed.

Margaret’s Kitchen, Again

When you confront a thief and the thief is your mother, there is no tidy grammar for the scene. There is the table where you learned to read. There is the chair you carved a tiny star into with a butter knife when you were nine and needed proof you could mark the world. There is the sound of your own pulse getting it wrong—too fast, then too slow, then pretending it’s normal when the math says otherwise.

I did not go back to Margaret’s house to fight. I went back to take an inventory of whatever honesty we had left.

She served coffee. I let it go cold. She apologized three times, each apology wearing a different dress: practicality, nostalgia, fatigue. The third dress fit the best. “I was tired,” she said, looking not at me but at the window where the bird feeder hung like a clock. “I am tired.”

“I believe you,” I said. “But tired people can still be wrong.”

She pressed the corner of a napkin into the rim of her cup as if the problem were a ring on the wood. “We were going to pay it back.”

“You picked a lock,” I said. “You didn’t borrow a cup of sugar.”

She flinched at the word lock. For the first time, I saw the fear under the choreography. Not fear of me; fear of herself. Of the person who could become small enough to justify a forgery.

“Do you want me to beg?” she asked, not unkindly. “Would that make it… even?”

“I don’t believe in even,” I said. “I believe in true.”

We didn’t fix anything. We also didn’t make it worse. That counts for something.

Teaching a Sky How to Behave

They brought me in to evaluate a training syllabus that had become too fond of its own bravado. Virtual reality can do a beautiful impression of courage; it can also make cowboys. I stood in a cavernous lab in the desert with a headset on and my hands in the air like I was receiving bad news, and I rewired a simulation so that it punished swagger and rewarded calm. When a pilot tilted toward showmanship, the wind shifted unfavorably. When a pilot breathed, the horizon steadied. You cannot negotiate with physics. You can befriend it.

At lunch, a first‑year asked what no one else wanted to say out loud. “Ma’am, how do you not get angry?”

I smiled, not because it was funny, but because the answer is so boring. “I get angry all the time,” I said. “I just put the anger in a place where it can carry something.”

He looked disappointed, like he’d expected a secret technique. There is one. It’s called practice.

The Photo on the Mantel

The press found the photo they always find: me in a helmet, a grin too wide for my face, arm around a woman whose name they didn’t print because they didn’t know it and I wouldn’t tell them. We were twenty‑two and reckless with joy, standing on a flight line in a country that was pretending not to break. Headlines called it “rare.” The rare part wasn’t that we were women. The rare part was that no one in the frame was trying to be the main character.

I called her that night. She answered on the second ring with the sound of a kettle in the background. “You’re on my television,” she said dryly. “Stop that.”

“I’m trying,” I said. “The jet did most of the work.”

“You always liked an entrance.”

“I like exits better,” I said. “They involve going home.”

“Come visit,” she said. “I’ve got an extra room and a dog that thinks it’s a cat.”

“Soon,” I said, telling the truth and a lie at the same time.

A Funeral, Corrected

I went back to Daniel’s grave alone on a Wednesday when the grounds crew was eating lunch in the shade of a maple and the only other visitors were a cluster of teen boys practicing skateboard tricks in the empty lot across the street. I brought no flowers. I brought the exact words I had wanted to hear someone say at the pulpit and wrote them on a notecard instead.

You were a brother, not a statue. You made messes. You made amends. We loved you. We were complicated. Your life was not a brochure. It was a life. Good job.

I left the card tucked under the corner of the stone, not to become soggy in the next rain but to sit there just long enough to say, briefly and privately, that the record had been amended.

Storm Sinks and Kitchen Light

Outside of the news cycle and the uniform that makes strangers stand up straighter, there is an ordinary apartment with an oven light that casts a soft gold on tile. There is a sink with a slow drain because I keep refusing to call the super. There is a bowl that used to belong to my grandmother—pearled edge, small chip at twelve o’clock. There is a grocery list with oranges and light bulbs and call the dentist written in my own careful print.

There is a city that wakes up early and doesn’t apologize for the noise. There is a general who makes her bed every morning because she learned young that chaos travels better when it has a crisp surface to set down on. There is a woman named Rachel who sometimes eats standing up at the counter and sometimes sits on the floor with her back against the cabinet because the dog that is not hers likes her to occupy the exact height where a forehead can be leaned upon.

The Girl with the Red Backpack

At Annapolis, a midshipman with a red backpack waited after a lecture until the room emptied. She had that look—the hovering at the edge of a question you’re afraid to ask in public. “Ma’am,” she began, then restarted with the thing that mattered. “My parents think the uniform made me mean. They say I used to be sweeter.”

“Maybe you were,” I said. “Maybe you were also smaller.”

She swallowed. “They liked me smaller.”

I nodded. “A lot of people will.”

“What do I do?”

“Be kind,” I said. “Not sweet. Kindness has a spine.”

She wrote it on her hand in tiny block letters as if she could carry it like a talisman into the next room where the next version of the conversation would be waiting with the same old choreography.

A Visit Pretending Not to Be One

My father took to fixing things in my apartment the way some men take to religion late. He would “happen to be in the neighborhood,” which is a phrase he had never used in my childhood because neighborhoods did not happen to him; he curated them. Now he knocked lightly and stood in the doorway with a toolbox and the fragile dignity of someone attempting to pay down a debt with labor.

“The mailbox flag looked loose last time,” he said once, unspooling electrician’s tape like a magician who keeps forgetting the trick. “The hinge too.”

“It holds,” I said.

“Let me make it hold better,” he countered, and I let him, not because the hinge needed it, but because he did.

We did not discuss Margaret. We did not discuss Daniel. We replaced a cracked outlet cover and called it a truce.

The Investigation Closes Its Mouth

JAG’s memo was clinical and correct. Administrative censure. Removal of access. Ethics remediation. No referral to criminal court. It would sting. It would also end. I read the last line twice: This office recognizes mitigating factors, including familial proximity and lack of personal enrichment.

I closed the file and said to the empty room, “That will do.”

The Thing About Forgiveness

People talk about forgiveness like it’s a door you either walk through or you don’t. It’s not a door. It’s weather. Sometimes you wake up and the air is so clear you can see for miles. Sometimes a fog comes in and you drive slowly with your hazard lights on because sight is not the same thing as safety. I do not know if I forgave Margaret. I know that the thought of her did not make my hands shake anymore. That’s a forecast I can live with.

Mason’s Volcano

I went. Of course I went. The gym smelled like old sneaker and school paint. Mason’s volcano was taped to a table with a hand‑lettered sign: Mt. Responsibility. His mother laughed when I read it. “He’s very literal,” she said.

Mason poured the vinegar with theatrical caution. The foamy red rose and spilled over the edge and the kids screamed like it was a small, joyful apocalypse. After, he tugged my sleeve and whispered, “General, do you think I can be both really good at things and not make other people feel small?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “That’s the assignment.”

A Field Where the Wind Is Honest

I stood at the edge of a training field in Texas where the grass grows in defiant clumps and the wind tells the truth sooner than men do. I watched a formation of new pilots make their clumsy first triangles in the sky. Every wobble felt like a prayer answered in slow motion. The instructor beside me—call sign Penny, because she was once strapped in with a coin stuck in her glove for luck—nudged my shoulder. “You’re smiling,” she said, mock‑accusing.

“I’m remembering,” I said.

“Good ones?”

“Enough.”

The Night the Power Went Out

In my apartment building, the power failed at 2100 on a Tuesday because the grid doesn’t care how your week is going. Neighbors opened doors into the hallway and created an impromptu summit meeting by phone flashlight. I fetched a lantern from the top of the pantry and lit it, the room going amber, soft edges reappearing.

A child down the hall cried. Someone’s sourdough died in an oven cooling too fast. Someone else began to sing without apology—a low, steady hum that sounded like the kind of lullaby you don’t learn, you inherit.

I stood at the window and looked across the river at a city that ebbs and surges like a tide. I thought of all the nights I had sat above a darker landscape with a radio pressed to my ear, trying to keep the lights on for people who were not yet ready to be the story. Some work is spectacular. Most is maintenance.

The Photo They Didn’t Publish

On my desk sits a photograph no one else will see: a group of us on a bleak strip of nothing, wind making our eyes water, exhaustion smoothing us into the same soft shape. In the foreground, a girl with a red backpack who grew into her bones. In the middle, a mechanic with grease like war paint. In the back, me—chin up in a way that somehow reads not defiant, not even proud, just present.

I look at it when the story tries to rearrange itself into something with too much noise. It reminds me that the plot has always been simple: show up, carry, set down, show up again.

The Reunion I Didn’t Attend

My high school class held a reunion in a hotel ballroom lit like a secret the hotel didn’t trust. A friend sent a photo. Daniel’s face on a memorial board near the bar; my name misspelled on a tent card at a table I wasn’t going to sit at. I made myself a sandwich at home instead and ate it standing up in the soft oval of light from the stove hood. It tasted like turkey and adulthood. It tasted fine.

The Long Walk

There is a path behind Fort Caldwell that soldiers take when they need to talk without being overheard by their own brains. Gravel, then dirt, then a narrow plank bridge over a creek that is more persistence than water. I walked it with Cross on a Friday, the two of us configured not as rank but as weathered humans who have shared a bad room and made it out with most of our edges intact.

“They asked if I wanted to transfer,” he said, tossing a pebble into the creek with Aimless Precision, a sport every soldier learns. “To get away from the noise.”

“And?”

“I said I’d rather stay and learn how to hear better.”

“Good,” I said. “Noise is a teacher if you let it be.”

He nodded. “You always make everything sound like a field manual.”

“That’s because it is,” I said, and we both laughed, a quiet sound that startled a bird from a branch and made it reconsider its afternoon.

The Letter I Did Send

Months later, I mailed a single sheet of paper to Margaret. The accounts are corrected. The locks are changed. If you want to see me, ask. Don’t appear. If you want to talk, write. Don’t perform. I don’t owe you forgiveness. You don’t owe me motherhood. We owe each other the truth we can manage.

She replied with a postcard of the chapel—sun striking the steeple. I will try to be brief and real, she wrote. It was not an apology. It was a first draft.

The Work That Remains

There is always more work. New pilots, old systems, a small boy who believes his volcano and his heart are both named Responsibility, a midshipman who wants to be kind in a world that confuses kindness with surrender, a father with a toolbox and a new understanding that hinges and daughters require different torque settings.

I file the JAG memo. I fix the sink. I buy the oranges. I sit on the floor while a dog I do not own falls asleep with his head on my knee. I answer one email from the reporter with four words: No comment. Doing my job.

Then I do it.

Cadenza (for Quiet Brass)

On a Sunday, the band in the park played a Sousa march as if joy were duty. A little girl with pigtails saluted every passerby with the solemnity of a tiny general, then shrieked with laughter and chased a bubble. I watched the bubble rise, iridescent and unserious, and thought of the chapel windows trembling and the way the air changed when a voice said my name like a headline that had finally learned to conjugate.

I am not an idea. I am not a correction in the minutes of someone else’s meeting. I am a person with a bed that is made and a uniform that is hung and a name that I now pronounce to myself with the gentle certainty of a promise kept.

If the jet were to come again tomorrow, I would board it. If no jet ever comes again, I will walk to work. Either way, the distance will be honest.

And if I pass a boy on a scooter or a girl with a red backpack, I will salute—not because of rank, but because of recognition. Some people you meet on the way up. Some you meet on the way through. The best you can do is see them in time.

PART III — Orders, Unclassified (A Novella in Brief Reports)

Report 1: Domestic Theater

Subject: Monroe, R. (Rachel).

Condition: Stable.

Action: Maintain perimeter. Reinforce boundaries. Do not escalate.

Notes: Family remains a low‑temperature fire. Feed with oxygen only when necessary. Deploy water sparingly. Sand works better.

Report 2: Operational Ethics (Annapolis Seminar #7)

Cadet Q: “Is loyalty to family incompatible with loyalty to mission?”

Monroe: “Loyalty to truth is the foundation; the rest are walls. Build your foundation first. The walls that can’t stand on it will fall and you will call that grief. It is actually architecture.”

Report 3: Maintenance Log

Mailbox flag: secure.

Sink: drains.

Hinge: holds.

Heart: holds.

Notes: Continue routine checks. Early detection prevents dramatic failures that look like plot.

Report 4: Weather

Forecast: Clear with variable convictions. Carry a jacket. And a pen.

Report 5: Press

Status: Persistent, polite.

Response: Politer.

Script: “No comment. Doing my job.”

Outcome: Story seeks louder subject. Good.

Report 6: Margaret

Incoming: Postcard with six honest words.

Outgoing: One sentence, three requirements.

Status: Armistice. Not peace. Not war.

Report 7: Cross

Observation: Listens more.

Risk: Will be promoted.

Mitigation: Remind him that altitude increases wind. Teach him how to lean.

Report 8: Rachel

Status: Present.

Orders: Continue.

PART IV — The Long Range Plan

Strategic plans look heroic on PowerPoint. In real life, they’re made of calendars and stubbornness. Mine has fourteen lines and fits on a yellow legal pad:

- Sleep before midnight when you can.

- Eat an orange every day.

- Write it down even if you don’t send it.

- Fix the hinge before it squeals.

- Teach one person to breathe.

- Learn one new name without asking their rank.

- Keep the red backpack sentence ready: Kindness has a spine.

- Call Penny. Call the mechanic. Call the one who brings you back to earth.

- Don’t go to the reunion. Eat the sandwich.

- Keep your boots near the door.

- Salute the right people.

- Forgive when the weather allows.

- Do the work anyway when it doesn’t.

- Repeat.

When people ask for secrets, I show them the list. They laugh. Then they try it. Then they stop laughing.

PART V — Last Light

Evening sits different in cities where the river throws the sky back at you like an answer. I stand on the footbridge as the day folds itself neatly along the seam of the horizon. Across the water, windows flare and dim in patterns that look random and are not. Somewhere a jet makes a line the exact length of a shift change. Somewhere a child names a volcano and decides not to be smaller to make anyone else comfortable.

My phone buzzes once with a text from an unknown number that resolves, after a second, into a known one. Proud of you. No punctuation. No name. I do not need one.

I put the phone back in my pocket, breathe, and walk home on legs that still remember dust and tarmac and the astonishing relief of stepping onto a floor that does not move.

The door clicks behind me. The room receives me like a fact. I hang the uniform. I fold the day. I turn off the kitchen light and leave the oven light on, just enough gold to find my way if the night asks.

That’s all a life is, in the end: enough gold to find your way. The rest is weather, which is to say—

—manageable.